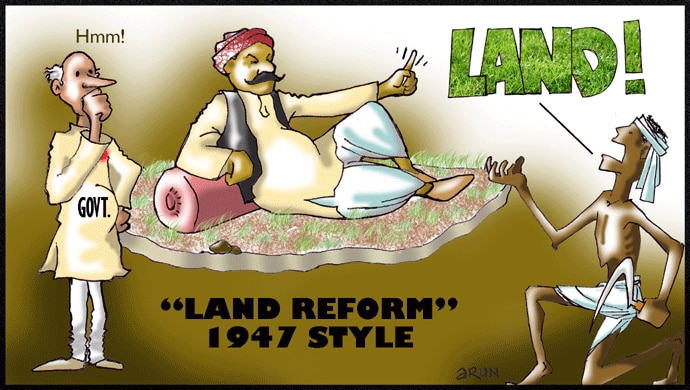

New Land Acquisition Bill is all about grabbing land from the tiller

Doublespeak is familiar terrain for the practiced politician and the aam aurat and aadmi is well inured to it. Nevertheless, the attempts by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and finance minister Arun Jaitley to sell the current Land Acquisition Bill as a pro-peasant reform measure seems to cross the normal boundaries of everyday political fuzzwording. While the Bill is widely recognised as a measure to fulfil the demands of the big industrialists lobby, the government is unrealistically trying to cloak it as a land reform in the interests of the farmers.

Forcible transfer of land to big corporations

"Forcible land acquisition has always been an issue of life and death for millions of people in India, not only farmers but also agricultural laborers and fish workers." This statement, from the press release of the organisations who had mobilised in thousands at Delhi against the Bill, about sums up the position of the rural populace in most parts of the country.

The amendments that are being brought to the Land Acquisition law are all intended to overcome any rural resistance and smoothen the path for the enforced handover of large tracts of agricultural and forest lands that are being eyed by big corporations for mining projects, special economic zones, industrial corridors, smart cities and other such projects. The changes include the removal, in most cases, of provisions for obtaining consent of affected people and for doing a social impact assessment of the project, as well as a relaxation of the clause for return of acquired land that remains unutilised after five years.

One of the more farcical arguments given by Jaitley is that of national security - that Pakistan would come to know of a project while consent of farmers and social impact assessment was being done. Since the same government is allowing Foreign Direct Investment in defence, the logic that an Indian farmer is more of a security threat than a foreign investor entity is difficult to swallow. As Medha Patkar, who led protesting farmers to Delhi, has replied, "the real battle is between farmers and land grabbing corporates, not between India and Pakistan".

|

"Land to the tiller" in 1947

This battle however is just another round in the longstanding ongoing war for land being waged in this country over many decades. The land hunger of the peasantry, particularly the landless and marginal peasants, was one of the principal aspects of the struggle for independence from British rule. "Land to the tiller", the popular slogan of the peasant organisations who formed the backbone of the freedom movement, originated from the antagonism of the rural masses with the British-nurtured landlords, who took the lion's share of the output without contributing anything to the production. The freedom fighters demanded that the one who tills the land must own it. It was also the war cry of the armed struggle in Telengana from 1946 led by the Communist Party of India. It was in this context that the Congress and its post 1947 government had to commit itself to a programme of land reform.

But, with the strong hold of big landlords over the leadership of the Congress, the sincerity of its commitment to land reform was always suspect. Though numerous legislations were enacted for zamindari abolition, security of tenancy and ceilings on land holdings, the loopholes left in the laws were numerous enough to ensure that no real redistribution of land took place. This led to another round of unrest in the late sixties and early seventies, with the Naxalite movement forcing the issue of exploitative land relations back on the country's agenda. A meeting of chief ministers in 1972 on Naxalism saw the then union home minister Y B Chavan warning that the green revolution may turn to red. This meeting then decided on a new round of land reform.

Land reforms after liberalisation

The new land reforms too did not take off and with the onset of liberalisation policies in the mid-eighties it became a forgotten agenda. As pointed out by a 2006 Planning Commission Report on Land Reform, the government found "it repugnant to talk about it, just in case the operators in the market get frightened by any state intervention in the land market." The same report pointed out that it was only a new spurt of rural violence led by the Naxalites that had brought the issue of land reform back on the national agenda of action.

Liberalisation had also brought in a new breed of land hungry operators - the corporate class - who were demanding prime agricultural and forest land for their projects at throwaway prices. The colonial era Land Acquisition Act of 1894 came in handy for the state to forcibly acquire land for private entities. As the scale of land acquisition reached mammoth proportions, it was again a government report in 2009 of the Union Rural Development Ministry that called it a land grab - the biggest after Columbus. Violent resistance against mega projects, SEZs, nuclear plants, and the like at Singur, Nandigram and other places shook up a number of governments and the ruling classes were forced to do a rethink. By 2013, the Centre was compelled to replace the 1894 law with an enactment that recognised the right of consent of the local populace and provided for some compensation and rehabilitation. It is the amendments to this 2013 law that are now under debate in Parliament.

|

Pressure on Modi to deliver and its consequences

Global big business, while backing Modi, has also been getting impatient. The Indo-US CEOs meet during Obama's visit end January was quite blunt in its demand that Modi must deliver - in ways profitable to them of course. Big industry chambers like CII and Assocham had unanimously welcomed the changes to the land acquisition law and would now want him to somehow ensure its passage through Parliament. Modi thus has put his whole weight behind it and will see that it is passed.

Getting it passed by society, and particularly the rural poor, is however quite another thing. Quiet acquiescence to acquisition is now quite a thing of the past. As subsistence for the poor in modern day rural India becomes more and more precarious, few are willing to give up the security that jameen and jungle provide. Almost every major project meets resistance from wide sections of society.

To deal with this the government strategy is almost completely reliant on the coercive arms of the state. Draconian travel restrictions and funding controls for environmental activists and NGOs, lathi-charges and even firings on the project-affected people who protest, civil-war style military force as per a Clear-Hold-Build policy for the Maoists, and some more, are all in store. Yet one wonders whether these will suffice to contain the anger and desperation of the dispossessed.