Ex principal of St Stephen's College explains why Rahul Gandhi is not cut out for politics

One day, we were told that St Stephen’s would have two sections, as against one, of History Honours students. No special reason was offered. None was sought.

Around the same time, an additional police chowki came up, nearly hidden in the arboreal secrecy of the Ridge named after Rahul Gandhi’s great grandmother, Kamala Nehru.

When the session began in July of that year, strange faces (strikingly non-academic in vintage) were seen here and there, much less obtrusive than their counterparts today, on the campus and in the corridors.

St Stephen’s had been, historically, hyper-sensitive to the presence of "outsiders" (always perceived as ‘intruders’) on the campus. Questions were asked regarding this unusual development.

The explanation established a connection between the ‘intruders’ and a fair complexioned first year History Honours student by the name of Rahul (he was far, far away from being RaGa then).

I was also told that he was admitted against the "sports quota" and that the handsome, young gentleman was a shooter.

Being of the faculty of English literature, I did not teach this privileged entrant into the college.

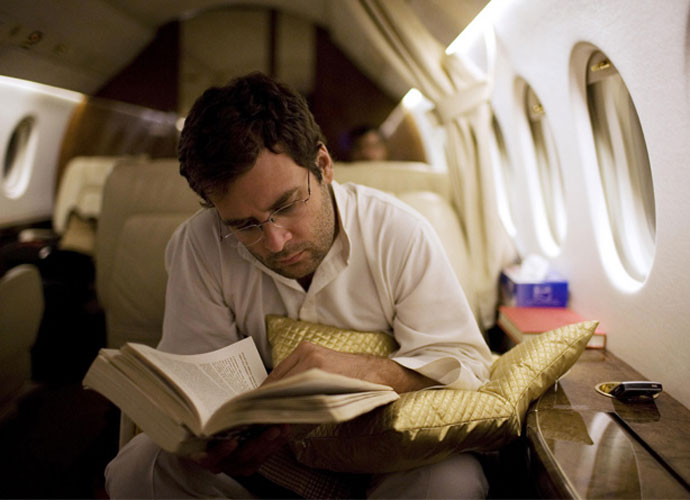

Rahul, like his father Rajiv, was unobtrusive by instinct.

It was as though he was unaware of the importance of being part of the Nehru clan. I happened to meet the police officer, who was in charge of his security.

From him I gathered that he, and his team, were under strict instructions "not to create any inconvenience to anyone in the college under the pretext of security."

They did not. (In contrast, the son of a political big-wig from Orissa, who studied in St Stephen’s in the ‘70s would not let anyone forget for long that he was highly connected. He too was of the Congress extraction).

Rahul left the college as abruptly as he had entered it. I was told that he had gone overseas to pursue higher academic purposes.

My first serious, face-to-face meeting with Rahul took place much later after he had been inducted laterally at the top of the INC. By then I too had trudged my bleeding way to the top of the college.

Several old students contacted me regarding an unfortunate statement Rahul had made, which reflected poorly (and unfairly) on St Stephen’s.

While speaking (I suppose impulsively) on what ails higher education in India, he had said that while he was in St Stephen’s, he was not allowed to ask questions in the class.

This surprised me.

My own experience was that the students were too engrossed, for the most part, to ask questions. I used to connect recondite texts to immediate contexts precisely to provoke discussions; without necessarily achieving the purpose to the desired extent as often as I would have liked.

|

| Rahul Gandhi left St Stephen's as abruptly as he had entered it. |

I decided to meet Rahul. We met. The meeting ended with our agreeing that Rahul should visit the college for a free, unregulated, hour-long interaction with the entire college community.

At this meeting, I listened to him attentively and critically. I could pick up occasional streaks of innocuous, well-meaning, tactlessness in his extempore unguardedness.

His overall theme was the need to "challenge and change" the status quo and to cultivate a spirit of questioning, with that end in view.

"Can anyone," he turned rhetorical, "bring about the slightest change in the politics of our country?"

Without pausing for a moment he pronounced an emphatic, "No".

"Can your principal," he continued, casting an innocent, sideways glance at me, "change a small college like this, in any respect? No . . ."

I was astonished.

I had been, ever since assuming responsibility for the college, involved in a life and death struggle to bring about some long overdue changes - radical and disconcerting to the eyes of orthodoxy - in the character and outlook of the college.

So, in my remarks, in the wake of Rahul’s speech, I said, "Of course, it is possible to challenge and change any system or institution; provided one is willing to pay the price for it."

The in-house audience, nevertheless, was so bowled over by his openness and humility (the girls, I surmise, a trifle with his handsomeness as well) that the formal interaction itself lasted over two hours.

Instead of rushing away at once, as VVIPs are required to do (even if they are in no hurry to depart) Rahul stayed on, savouring the occasion for nearly an hour thereafter.

This itself convinced me that the young man was not really cut out for politics.

He is an exceptionally good human being. He means well. He wants to improve everything, including himself.

But he is not cast in the familiar political mould, lacking distinctly in that quintessential touch of belligerence (which shines even though gestures of hypocritical courtesy that make, strangely, all else feel small) in one’s mien and manners, that touch of low cunning (that while looking at you, sees not you, but what you could be converted into), that studied practice of "tact" (which, in common parlance, is called unconscionableness), that overpowering rhetoric, or at least that capacity for piercing sarcasm soaked in sugar-coated nihilism, or the uncanny ability to snatch the heart-strings of the audience and play on them tunes beyond the raga (or should I say RaGa) of integrity.

To me, he seemed like a lamb among wolves. (By the way, this, for God’s sake is a metaphor and not a literal statement.)

I met Rahul, for the last time, in the wake of the Commonwealth Games (2010) scandal, the long talons of which had hurt St Stephen’s too.

I urged him to come out in the open and take a stand against corruption.

"They are selling," I warned him, "your future, piecemeal. Now is the time, or never."

I awaited his response. He was thoughtful for a while, staggering, as it seemed, under the imagined enormity of the prospect. I saw a man pulled painfully in opposite directions.

His soul, I knew, wanted to strike out and speak up. But the training he has had by then, the training that kills the human in those who aspire to be "political", shrieked against his conscience.

The "still, small voice" that speaks within each one of us, "the inner voice" that Sonia Gandhi could hear in 2004, but never thereafter, stands no chance at all against its stridency.

The inner struggle ended in the course of one, long, nearly eternal minute. at the end of which Rahul asked me (the political speaking through him now), "Do you want to meet the president of the Indian National Congress?"

"No," I said and I bid goodbye, never to see the gates of No 10 Janpath ever again.

I knew, in a strangely compelling way, that the dice were cast. That destiny was loaded. That, somewhere in the west, the sun was about dip into an ocean of forebodings.