Why Indian railways makes us travel back in time

Tea is the quintessential ingredient of an Indian railway experience. In the firm Dil Se (1997) it becomes the arbiter of an ephemeral bond - "the world's shortest love story" - between the protagonist-lovers.

Drops of isolated rain splash into the tea cup, held by Khan, as Manisha Koirala looks away, from inside the compartment.

The narrative of tea inscribes the narrative of global capitalism in India, and of labour in the Indian railways. This nature of representation - through a metonymic device - has been extremely common in the history of the railways.

However, a "standard Indian Railway cup of tea to be served with a standard Indian Railway Breakfast" is not so standard after all.

|

| Drops of isolated rain splash into the tea cup, held by Khan, as Manisha Koirala looks away, from inside the compartment. Photo: YouTube |

There is great diversity in the cries of "chai, gurram chai," (or more recently, "khurrab se khurrab chai, sabse khurrab chai"), as well as in the materials tea is served in - plastic, paper, polystyrene or earthenware cups.

The first major experiment of the Indian Tea Association (founded in 1881) for globalising tea began in the railways. In 1901, India was designated as a "potentially large market for tea."

In 1903, the Tea Cess Bill was passed regulating a cess on tea exports, which would then be used for tea promotions in India and globally.

After World War I, petty contractors were provided with tea packets and kettles to serve at the chief railway junctions of Bengal, Punjab and North West provinces.

By the 1930s, the "Tea Association proudly pronounced the railway campaign a success," concluding that "a better cup of tea could in general be had at the platform tea stalls than in the first class restaurant cars on the trains."

It put on display hoardings and posters for recipes of tea, in Indian languages, on railway platforms. Some of these exist even today, such as those at the stations of Ballygunj, Dum Dum, Naihati, Bongaon, Santipur and Ranaghat, in and around Calcutta.

|

| Tea was transformed into a typical Indian phenomenon over time. Photo: Reuters |

Tea, that was a vital commodity and signifier of English imperialism in India, became a hybridised entity as Indian vendors customised the colonial recipe. Defying the advice of their English instructors they used more milk and sugar, to appropriate the taste of the Indian buttermilk or lassi.

Tea was transformed into a typical Indian phenomenon, one that often singularly characterised the ancillary-industries emanating from the railways. The Indian population had remained largely alien to the taste of tea till the 1900s.

But, by the end of the twentieth century, it was consuming over 70 per cent of its own produce of the crop.

Thus, the English breakfast tea became the Indian morning or midnight tea, naturally determining the cinematography of popular Indian soundtracks, featuring small-town railway stations of Kumaon, Garhwal, Monghyr, Mughal Serai, or elsewhere - romantic landscapes drenched in rain or shrouded in fog.

|

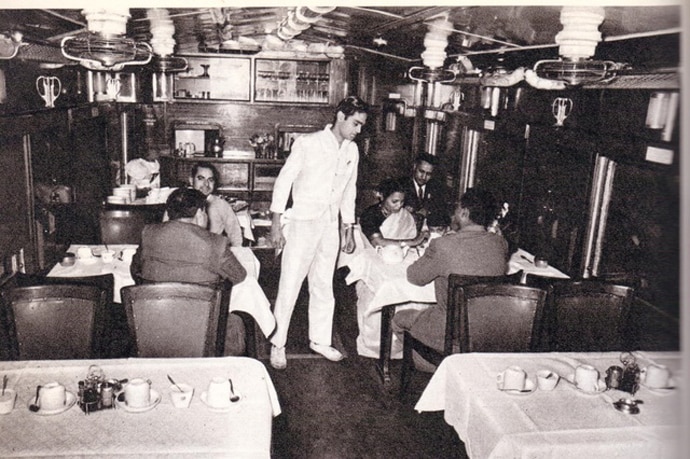

| Inside a restaurant car of the Indian Railways in the 1940s. Photo: IRFCA |

The mechanisms of railway representation have percolated so deep in the Indian psyche that "[t]he chai wallah is still the first thing a passenger hears on waking up in a train in northern India as he marches through the carriages, a metal kettle swinging in one hand and glasses in the other, calling out 'chai-chai-chai.'"

However, such a chord seems to be strung with an essentially colonial or nostalgic harmony - or looking back in anger with a post-imperial perspective - when the refrain of the chai-wallah's alarum, and the inappropriateness of the Indian railway tea-recipe is found, mostly in Western researches or narratives.

...tea vendors crying "Chai, chai, chai" along the corridors and from the platforms of every station passed through all hours of the night...Anyone who has ever travelled on an Indian train could identify with the chai thing. One man comes along carrying a tea urn. You can hear him from the other end of the carriage...It is a deepthorated, high-pitched scream. I swear there must be a voice training school for them somewhere on the outskirts of Delhi. Anyway, after bellowing their way through the carriage, causing the utmost annoyance, they stop and look at you and in their normal voice ask "Chai?"...And after one goes, another arrives; then another and another. Good God, how much chai do they think a person needs? And I wouldn't mind if it was decent tea, but it is not. They must destroy it by putting four spoons of sugar into each small cup. For a country that grows so much tea, Indian Railways does not seem to have conquered the art of making a decent pot yet.

The paraphernalia of the culture-industry associated with the railways are layered in the Indian consciousness as intricately as the dressing of condiments in a typical Indian curry.

Indeed, the memory of the railways is pickled with - apart from many other elements - a culinary aspiration.

|

| The Purveyors of Destiny: A Cultural Biography of the Indian Railways; Arup K Chatterjee; Bloomsbury |

According to Lizzie Collingham "[o]ne of the places where Anglo-Indian cookery really came into its own was on the railways...The standard of the food served at the station restaurant and in the dining car was similar to that provided at the dak bungalow."

Her predecessor on the history of the curry in colonial India, Jennifer Brennan, notes how trains stopped at stations beyond civilisation, and even there, in the midst of the "hissing of steam and the occasional slamming of doors," a man would walk up the lobby with cries of "Lunch, lunch!"

While lunch comprised leftover roasts from previous nights, called cold meat, dinners were better organised in the form of "thick or clear soup, fried fish or minced mutton cutlets with a bone stuck in, roast chicken or mutton, custard pudding or soufflé."

Considering the stamp of British approbation, railway restaurants have often served, as Collingham observes, as "clandestine spaces for experimentation," of dining in forbidden spaces, and of forbidden hands and food.

Likewise, Prakash Tandon notes how he, as a young man, saw vegetarian-looking businessmen coming into railway restaurants to eat omelettes, mutton chops, or drink alcohol.

|

|

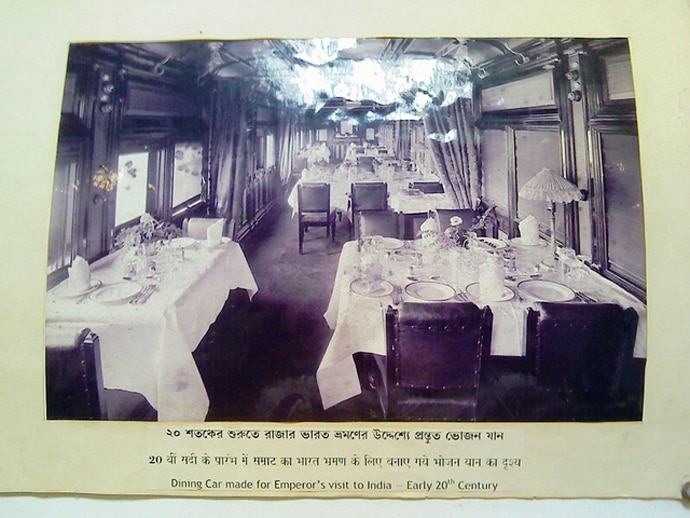

| The British Raj's great Indian train journey. Photo: IRFCA |

Brahmins readily lost their caste in the railways, and the railway refreshment rooms, possibly in cultural reverence of the memory of the Raj.

Besides being a grand experiment for maintaining racial segregation, the railways also served to communally segregate the Indian population, sometimes inadvertently.

British officials encouraged developing a culture of respect towards Hindu and Muslim attitudes to consumption.

Accordingly, while refreshment rooms were strictly segregated for first-class, second-class and Indian passengers, Hindu and Muslim passengers in all Indian railway stations drank water from separate containers.

Even tea supplies to Hindus and Muslims were carried out through separate windows, and tea stalls were divided into Hindu and Muslim openings.

Ironically, the Indian descendants of the colonials have retained much of the cultural repertoire of railway norms, particularly in the way food and drinks are catered on the Indian Railways.

Whether British or Indian, we are often Anglo-Indian (in the cultural sense of the term) while recounting our railway experience.

(This is not intended as a reductive statement on the cultural importance of the Anglo-Indians, whose association with the Indian Railways has been discussed at length in the book).

This is to say, a typical Anglo-Indian narrative following the tone of "In those days, et al" resonates with many of us from until the last generation to have boarded trains, rather than aircraft.

Titled Haunting India, Margaret Deefholts's recollections, of being part of the Anglo-Indian community, are rife with allusions to the indulgences in a world of the past. Her memory is coercive to the exact use of those residual colonial artifacts and signs, linked to the railways.

As French thinker, Jacques Derrida, might have observed, they are untimely, like ghosts.

"Hauntology" takes on a new meaning here. "To haunt does not mean to be present," according to Derrida, "and it is necessary to introduce haunting into the very construction of a concept... That is what we would be calling here a hauntology. Ontology opposes it only in a movement of exorcism. Ontology is a conjuration."

This profound thesis has a strange, but simple application in railway semiotics.

Railway nostalgia relies on signs - the badge, the logo, the cutlery, the disappearing ashtrays, the magnetising potential of railway tracks when a coin is laid between them and the wheels of an engine.

These signs are not only represented in their absence but are reiterated in order for the bygones to haunt the present. The signs of imperialism, theoretically, have an ontology - true!

But we cannot reach there. Our journey is mitigated by a conjuration of railway imagery. Representations of the railways haunt, but they also shackle.

They inter in themselves, along the way, tales of exclusion, narratives of the underprivileged, and toils of the labour forces, often grossly underpaid.

|

| Representations of the railways haunt, but they also shackle. Photo: Reuters |

The imperial face of the railways comprised uniforms of the stewards, visages of sahibs or memsahibs in alpaca coats at the railway platforms, the interiors of the railway cars and the colonial-styled bungalows that the passengers were bound to or were coming from, et al.

All these added to the complex infrastructural mechanisms of colonial science and heraldry, cartography, landscaping, historiography, geography, trade and pleasure-travelling.

Deefholts's tone is serene and seemingly benign.

When it was necessary to stay overnight before making a train connection, we were accommodated at the Railway Officers' restrooms at the station. In those days they were impeccably clean…and the Railway station dining rooms had heavy cutlery, and crockery/glassware embossed with the insignia of the Indian Railways. The bearers (waiters) wore starched white jackets, and their belts and turbans were surmounted by a badge or buckle with the Indian railways logo...[B]reakfast now comes pre-packaged in a soggy cardboard box containing an equally soggy "amlet" and leathery "toas." Gone forever too, is beef curry with fluffy scented rice - and also vanished, alas, is the best caramel custard in the universe.

The illusory site of desire she locates in another time is unfathomable for many, since new generations of Indians might seek comfort in the very packed cuisines that are disavowed by her.

Besides, she furthers the chain of nostalgia - a hankering after colonial signs - in the guise of the woes of a political transformation in the Indian Railways, and the subsequent loss of prestige in travelling therein; unlike what it used to be for families of second or third generation railway officers, or British officials.

Princely recollections of culinary fetish are also found in Maharani Gayatri Devi's Memoirs (1995).

Here representing food-in-transit is an inadvertent strategy of asserting imperial supremacy over consumption.

In the Memoirs, the audial paraphernalia of eating on the trains - the well-known "chink of cutlery" - comes across with perfect élan, more than the cuisines themselves. The neatness with which food was parcelled signifies the neat structures of labour behind the realisation of the railway curries:

The cooks prepared "tiffin carriers," a number of pans, each holding different curries, rice, lentils, curds and sweets. The pans fitted into each other, and a metal brace held them all together so that you could carry in one hand a metal tower filled with food... You could give your way to the railway man at one station and know that your instructions would be wired ahead to the next station, and that your meal would be served, on the thick railway crockery, as soon as the train pulled into the next one... Another waiter would be ready to pick up empty containers, glasses, cutlery and plates at any further stop that the train made.

Towards the end of the 20th century, train travel became "the de rigueur for many princely households, several of whom had their own private saloons."

The modes of eating on the trains "reflected a new gastronomic sensibility," with the development of railway travelling by the British and upper class Indians.

Postcolonial nostalgia for provisional Indian or continental meals, packed in aluminium boxes served by the Indian Railway Catering Services, evidently goes back to colonial palate-teasers such as the Railway Lamb Curry.

|

| Ironically, the Indian descendants of the colonials have retained much of the cultural repertoire of railway norms, particularly in the way food and drinks are catered on the Indian Railways. Photo: Internet/Independent Blog |

Undertones of aristocracy-in-proxy - the thrill of being served meals, blankets or paper-soaps-are immanent in every recapitulation of a railway journey, from a time when railway travel was infrequent not because of growing affordability of airlines tickets, but the limited necessity and scope for travelling, even for the urban middle-classes.

An extensive narrative of labour - of vendors, khansamas, bheeshtis, railwaymen, caterers, and so on - is subsumed by the aristocratic labour of nostalgia, which characterised over half a century of postcolonial Indian mobility. They still possibly do.

A late enthusiast of Anglo-Indian recipes enumerates these associational and aspirational aspects of activity aboard the railways in her annotation on the Railway Lamb Curry, which she perceives as:

...a direct throw back to the days of the British Raj, when travelling by train was considered aristocratic. The very name "Railway Lamb Curry" conjures up scenes of leisurely travel by train in the early 1900s, of tables covered with snow white table cloths laid with gleaming china and cutlery, of turbaned waiters and bearers serving this tasty slightly tangy Curry dish with Rolls and Crusty White Bread in Railway Dining and Refreshment Rooms and in Pantry Cars in long distance trains…[besides] this very popular and tasty dish was prepared and served...only in First-class Cabins…with Bread or Dinner Rolls.

The culinary accent has a dual function.

First, it is an assertion of the finesse in the mobility of colonial architecture.

Cutlery and upholstery, fish and poultry, and conduct and atmosphere, of British affectation-in-transit articulate conquest over space and time, without compromising on practices of exhibiting racial distinction.

Food and its rich consumption, in flux, perform as the insignias of coloniality.

|

| Murder on the Orient Express (2010) |

A 2010 documentary on the Orient Express, commemorating Agatha Christie's Murder on the Orient Express, featuring David Suchet in Hercule Poirot's seat, is a mélange of soufflés, Sancerre, bacon and exotic fruits.

Throughout Poirot's journey from London to Prague, the reiteration of "a time gone by" and its close alliance with menu cards and savouries observe the same trope of reclaiming the culinary as a means to reaffirm the bygone imperial.

Nostalgia of the Indian Railways, although removed in space, and belated in time, come from the same schooling.

The statement begs the question: if nostalgia for the railways is to be treated as a crucial measure of railway culture, have we already moved into a domain where the railways are a thing of the past?

Second, it perpetuates the reification of labour. Accordingly, labour forces of railroad history are meant to be usurped into a memory of personal aristocratic adventures.

The motif of culinary details has a very subtle role in accentuating architecture, and those of architecture in establishing imperial superiority and monumentality. What is meant by "architecture" here, is the cultural methodology of the upwardly mobile travelling class in ascribing values of desire and harmony to the interiors of the mobile railway compartment.

The custom is not altogether postcolonial. Its antecedents lie in Anglo-Indian railway narratives from the second half of the long Victorian century.

One such, The European in India or Anglo-Indian's Vade-mecum (1878), a travel and healthcare handbook, styles the interiors of a first-class compartment as adequately "supplied with silk curtains, venetians, gauze blinds, and glass, to be used at pleasure, with the view of excluding the dust, glare, and heat."

|

| Mark Twain's captivating descriptions of Anglo-Indian railway architecture had many precedents. Photo: Reuters |

In addition, the writers inform of the coming of "window screens made of the sweet-smelling Kus-Kus", suggesting a welcome hybridisation in the railway technology of the Raj, with Indian practices.

The profiling of the railways as lavish and commodious also became the task of the American author, Mark Twain, who travelled extensively in India, making arduous train journeys in the hill stations of India, going up to Darjeeling.

On each side of the car, and running fore and aft, was a broad leather covered sofa - to sit on in the day and sleep on at night. Over each sofa hung, by straps, a wide, flat, leather-covered shelf - to sleep on. In the daytime you can hitch it up against the wall, out of the way - and then you have a big, unencumbered, and most comfortable room to spread out in.

Twain's captivating descriptions of Anglo-Indian railway architecture had many precedents.

Outside India, Arthur Conan Doyle had begun weaving the fairytale gossamer of railway sequences through his eye-witness narrator, Dr John H Watson.

And the physiognomy and mobility of Sherlock Holmes embodied the architecture of Victorian English transport.

(Excerpted with permission from Bloomsbury)