What madrasa educated youth think about going beyond Islamic scriptures

Many feel madrasas must give lessons in math, science, computer applications and English to increase employment chances for students.

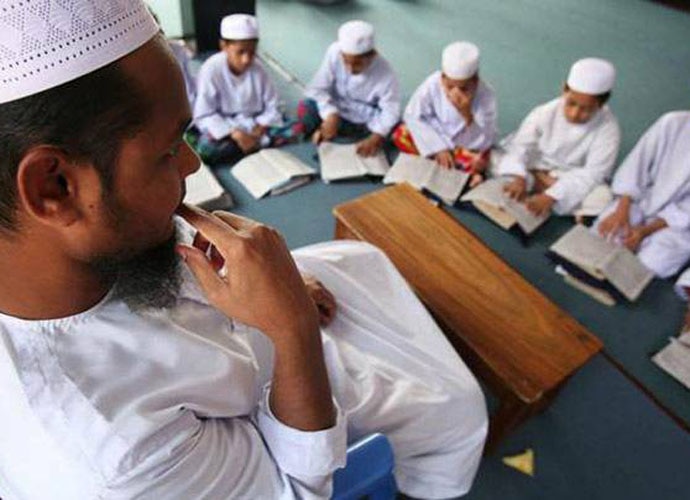

The debate on mainstreaming madrasa students has always been dominated by polarised rhetoric around learning “modern” subjects in madrasas. In principle, the madrasa modernisation policy supports learning in math, sciences and social sciences, in addition to religious education. Sceptics, however, have been suspicious of any policy intervention in madrasa curriculum as an attempt to dilute the religious nature of education. For long, the voices of madrasa students and graduates have remained ignored in these debates.

How do madrasa students, who have participated in the mainstreaming process, look back at their madrasa education and "modernisation"? To find answers, I spoke to some madrasa graduates studying in the Arabic department of Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Salman, a doctoral student, reflected on his journey from the madrasa to the university: "When I entered university after graduating from a madrasa, my beard became shorter. I would wear kurta-pyjama only on Fridays," Salman remarked with a grin, as his group of friends burst into laughter.

He paused for the laughter to subside and then continued: "Our madrasa trained us to uphold the principles of Islam in our life and work... to be a good Muslim... There were no restrictions on our choices of higher education and profession that we wanted to pursue." He paused again and said: "I want to clear the National Eligibility Test and become a lecturer in Arabic."

Salman and his group of friends belong to the growing population of madrasa alumni, who are opting for regular university education after graduation. Most of his batchmates continued within the fold of Islamic higher education in India and West Asia. Some also began practice as imams and preachers in mosques. He attended Jamia Islamia Sanabil, a large and prestigious madrasa in the Jamia Nagar locality of Delhi. Sanabil accommodates over 700 boys from mostly lower middle-class, north Indian Muslim families. The Islamic and Arabic education provided in the madrasa focuses on memorisation and exegesis of Islamic scriptures and their commentaries. Also, teaching in subjects like English, Hindi, math, natural and social sciences are offered- but only up to the secondary level.

The degree offered by Sanabil is not accredited at par with school examination boards, and its graduates are not eligible for admission to most universities. Nevertheless, institutions such as Jawaharlal Nehru University, Jamia Millia Islamia and Jamia Hamdard recognise Sanabil's degree for admissions to certain programmes. Traditionally, its graduates have secured admissions in programmes offered by departments of Arabic, Urdu, Persian and Islamic Studies.

Akbar, a PHD scholar in the Arabic department of JNU, is another student who chose regular university education after graduating from Sanabil. He feels that the degree of a good university is crucial to validate his talent as a writer.

He reflected: "I developed an interest in writing articles on social themes through the lens of Islamic philosophy, and my writings focused on offering solutions to social ills. In Sanabil, I wrote an article on the importance of education that was published by a local Urdu magazine. I was also the editor of the student magazine in Sanabil. I feel having a 'doctor' in front of my name is necessary for others to engage with my writings seriously. Right now, publications in the Urdu newspapers and magazines are under the monopoly of the older generation of Muslim intellectuals."

Imran, an undergraduate student in the same department, had the option of becoming an Arabic teacher in a madrasa at his native village in Uttar Pradesh. But he chose university education because he wanted to work in a city. Many madrasa graduates work in jobs that require proficiency in Arabic. These include jobs in BPO centres that handle operations of Arab firms and translation work in embassies of Arab countries. Most of them are located in Delhi.

Imran said: "I am not sure if I want to be in academics. There are some job opportunities that require knowledge of Arabic and I am interested in them. JNU gives us an edge in these jobs because we improve our English here and learn computer skills. And Sanabil gives us a strong grip over Arabic."

While these students seek to achieve diverse professional ambitions through their university education, they bear a palpable commitment to continuously engage with knowledge on Islam and its sciences. The affinity for their madrasa education continues in the university. JNU gives them access to academic resources and information technology that was unavailable in the madrasa. And a liberal environment provides them a fertile space to research and write on issues relating to Islam.

Hussain, A PHD scholar, is using this to build his PHD thesis on digitally produced Islamic literature.

He said: "I was free to use the internet and discovered a large body of critical commentaries on Islamic scriptures, Sharia and other Islamic sciences, and so many different interpretations of the same text."

Hussain feels that the Islamic education in madrasas is outdated and wants to bring in reform. He said: "After my PHD, I plan to initiate a research centre that will work on creating an updated syllabi. Some madrasas are still teaching commentaries from the 8th century and the focus is on rote learning rather than critical engagement. I am also planning to work on creating short-term courses on writing and research skills for madrasa students so that they can scientifically and intellectually engage with Islamic texts and commentaries."

Hussain's desire for reform emphasises on the "deeni" (religious) aspect of madrasa education. But these students also have strong opinions on the relevance of its "dunyavi" (worldly) element.

Most of them started off in smaller madrasas that did not have the resources to offer learning in math, science, computer applications and English. After coming to Sanabil, they appreciated the importance of learning beyond Islamic and Arabic education. They agree that madrasas need to give better training in these subjects for enhancing the employability of their students.

However, they believe that learning in these subjects should complement, rather than dominate Islamic education. As Umar, an undergraduate, remarked: "If someone becomes an expert in Islam, but cannot use the computer, does not know how to read in English or Hindi, how will he communicate his ideas. These subjects are also important to be a real Islamic scholar."