In which Neil Gaiman twists age-old fairy tales to wake the reader up

Can something as monotonous as sleep be a tool to access power? Fairy tales are perhaps the simplest vessels, to hold our dream worlds, our utopias, from child to child, from generation to generation. But what if the innocent fairy tale, instead of passing on dreams or ideals, becomes a vessel for silencing dissent in a child? What if the story that the child hears becomes the compass for his idea of right and wrong, of crime and punishment?

For instance, it has been well-documented that the concept of "wickedness" in female characters, especially in stories like Snow White, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, helped ostracise women whose "unfeminine" traits were deemed to be dangerous. Thus the myth of the desexualised, chaste, sex-starved woman was born. Every time the teller imposed his or her own censorship on these tales, they took away a little power, a little agency from the young women who listened. They were being put to sleep, unable to resist the subtle repression they were subjected to.

How did the listeners wake up, then?

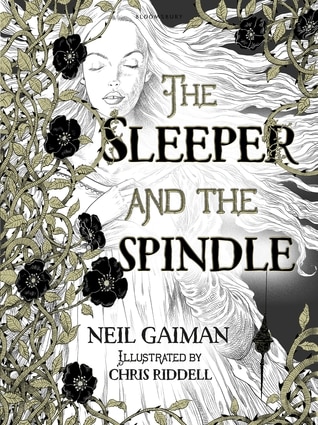

They woke up by reading people like Neil Gaiman. His latest book, The Sleeper and the Spindle, is dedicated to his "daughters who woke him up". And through his luminous retelling of two popular fairy tales - Snow White and Sleeping Beauty - Gaiman puts forward a compelling case, asking readers to wake up to the harsh realities of these stories. Gaiman's story begins with a queen (it is implied that this is Snow White, years after the events of her own stories) who is about to get married, something she isn't terribly keen on. She is politically powerful, decisive and she wants to take control of her own destiny. This, then, is the exact opposite of a typical lost-little-girl trope.

Through Gaiman's expert plot twists, we see Snow White coming to the rescue of a young girl who has been magically put to sleep by a vindictive witch. It would be pertinent to keep in mind that fairy tales played a pivotal role in Victorian debates of class and gender; think of writers like Dickens who were aware of the way fairy tales were circulated, and the liberties taken by every successive teller.

Grimm Brothers' fairy tales (first published in 1812) were meant to be told by grandmothers, spinsters (the name derived from their task of spinning cloth) to children, in order to softly reinforce cultural patriarchy. Wisdom resides in the old and the sexless; this is taken for granted. Sleep and comforts come to those who conform to these ideals, and this is where one might ask: What of the so-called "witches" or stepmothers or infertile women driven to the margins, who exercise this very weapon of sleep to avenge those who have taken their sleep away?

The problem doesn't lie only in the demonisation of the witch-prototype, but also that this is the only aspect we see of them, just as we see passive, fair princesses waiting to be "rescued". Although the practice of burning women branded as witches hasn't quite left many places in India, people are realising their mistakes. Spin-offs that show "witches" in a better light are not uncommon among regional-language writers, as well as both literary and popular fiction in English. (A particularly nuanced example of the same is Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar's novel The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey.)

Gaiman opines that his tale doesn't need a prince to rescue a princess. We, the readers need to rescue the tale from its saccharine-laden telling. His fictionalisation of the witch is commendable for its class-conscious overtones. This woman, who curses Sleeping Beauty, does something much more than just steal the princess's youth. Her spindle is an instrument to spin the tales of the comfortable upper-class people and put them to sleep where they can be then "disciplined" and she would have greater access to their resources, which have been denied to her since a thousand years.

Moorings of this kind also explore the idea of "choice". Snow White (the bride-to-be); through her decision to head Far East with the dwarfs instead of the west which is nearest to her palace, where her wedding shall be solemnised, is capable of intervening with power. After Sleeping Beauty is rescued from the spell, it's not very clear whether Beauty will survive her re-entry into a normal world. But Snow White has made her peace with the consequences of her decision. "There are choices, she thought, when she had sat long enough. There are always choices. She made one." All those years ago, in Sandman, Gaiman had told us "Sometimes you wake up. Sometimes the fall kills you. And sometimes, when you fall, you fly."

Storytellers like Gaiman, then, are doing their bit to make sure that the dream, a world where women aren't systematically oppressed, stays alive and kicking.

|

| The Sleeper and the Spindle, Bloomsbury, Rs 450. |