How Emergency brought India close to losing a freedom we take for granted

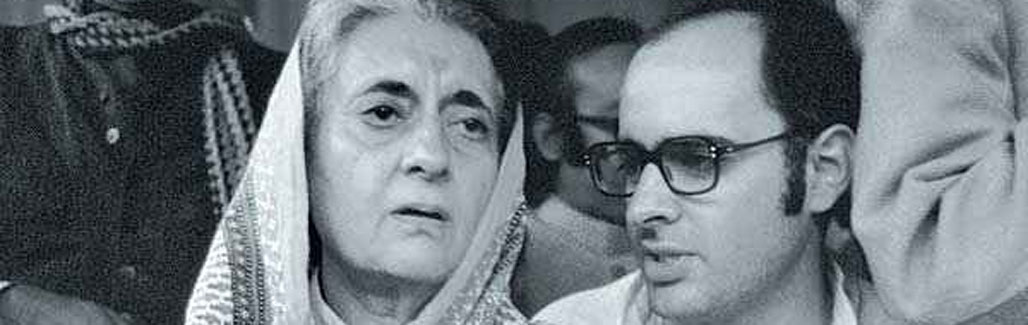

Voters vented their anger in the polls, but the country lay prostrate before the 'Empress' and 'Princeling' during those 19 months.

George Santayana's aphorism "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it" is yet again felt as the 40th anniversary of the most odious chapter yet of India's post-1947 history is upon us.

Constitutionally unseated from her Lok Sabha seat on June 12, 1975 after Allahabad High Court Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha's verdict holding her to be guilty of misuse of government machinery for her election, Indira Gandhi struck back imperiously, unconstitutionally and brutally. Political discontent against her government brewed during 1973-'75, and was only increasing across the country.

Student unrest triggered by Gujarat's Nav Nirman movement (December 1973-March 1974) against the then chief minister Chimanbhai Patel heralded the beginning of seething discontent against Indira Gandhi's government, though the Congress' troubles transcended Gujarat. March-April 1974 saw anger against her regime traverse eastwards. In stepped the redoubtable Jayaprakash Narayan. In April 1974, in Patna, JP called for "Sampoorna Kranti", exhorting students, peasants, and labour organisations to join in what he perceived would be a mighty heft at transforming Indian society. To the Congress dictator, this was no less than a clarion call to arms. A month into JP's call came the nationwide railway strike, spearheaded by another dynasty bugbear George Fernandes. Few among today's generation know that this strike was brutally suppressed by the Congress regime. Thousands of railway employees were thrown behind bars; their families driven from their quarters.

The gnawing away at democratic institutions and constitutional safeguards had been underway for some time. The halo of the 1971 triumph over Pakistan took time to dissipate, though the sheen was off by 1973. The "Empress" had little compunction in turning on the judiciary too. The landmark Kesavananda Bharati case overturned her government's 24th constitutional amendment of 1971. She responded with the appointment of AN Ray as the chief justice of the Supreme Court, superseding seniors JM Shelat, KS Hedge and Grover - the majority that had ruled against the government's parliamentary assault on the basic features of the Constitution. The midnight knock of June 25, rubber-stamped by a pliant President Fakruddin Ali Ahmed, and acquiesced to by her grovelling party, then followed.

June 25, 1975 revealed that the democracy most Indians were proud of could be shackled. It may be difficult for today's generation to even comprehend how dangerously close India had come to losing it for good. The cult of the "Great Leader" (Indira Gandhi) was reinforced by the more odious one of the "Little Great Leader" (her son Sanjay), who institutionalised state thuggery in politics, making no attempt to cloak his contempt of intellect and naked admiration for raw muscle.

Indira's humbling in the 1977 general election is strangely touted as proof of Indian democracy's resilience. A comforting thought; voters vented their anger in the polls, but the country lay prostrate before the "Empress" and "Princeling" during those 19 months. The only real opposition to them was from the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), whose role in confronting Indira is still a touchy subject for the self-important and thoroughly alienated "intellectual" class.

It is no less obnoxious that the political legatees of the anti-Emergency struggle are no custodians of democratic freedom and constitutional values. A glance at some of those who were supposedly shaped by that movement is sufficient to expose the posturing. A gerontocracy of casteist and roguish elements that still afflicts India's polity comprises those who were once part of JP's movement. Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar (once hailed as the a development messiah), self-styled heirs to the JP mantle have no qualms in cohabiting with the Congress, which till today have refused to apologise to the nation and its people for its endeavour to bring tin-pot dictatorship to India. VP Singh, another claimant to the JP halo suffered no pangs of conscience in courting Vidya Charan Shukla, a notorious Sanjay Gandhi protégé, in his journey to fulfil his prime ministerial ambitions. That VP Singh too was a Sanjay product was quickly forgotten by the very people who had forgotten Indira's mangling of their basic freedom and returned her to power emphatically in 1980, a mere three years after ousting her. The civil services were no less culpable. Civil service officers indicted by the Shah Commission had little trouble rising to successful careers. The role of the press, barring the few notable exceptions, was one of a crawling supplicant.

"Iron Man" LK Advani, information and broadcasting minister in the 1977 Janata government had no small role in ensuring Indira's return, providing her more than generous television coverage in her hour of exile. The sudden concern of the wannabe "Loh Purush" that the Emergency may happen again has less to do with any overriding love of democracy, a matter on which little elaboration is needed. It is impossible to share the propagated wisdom that the 1977 verdict is a safeguard against any future assault on democracy. Two instances - Rajiv Gandhi's brazen anti-defamation bill of 1988 and the blatantly anti-Hindu communal violence bill of 2011 - are proof enough of the inherently totalitarian DNA of the recently ousted dynasty that continues to be courted by forces for whom democracy is but a veneer.

Most crucially, the role of the Indian judiciary in allowing the Emergency to happen cannot be glossed over. The highest judiciary of the land covered itself with undying infamy in its capitulation to the executive of the day. Had the apex court showed spine, Indira Gandhi's dictatorship would have evaporated. It chose to bend and the pusillanimity of those few individuals ensured its ignominy, which it can never live down.

The sweeping lessons of the 1975 Emergency? To slightly rephrase renowned historian Will Durant, democracy is a precious thing, whose delicate and complex order and freedoms can at any moment be overthrown by those inimical creeping in from outside and corroding it from within.