If I were Arvind Kejriwal I would resign as Delhi chief minister

How did a man — a man who was once my hero — suddenly become the most disliked Indian? How did a protagonist steering national change become a people’s antagonist?

Let’s recall the Arvind [Kejriwal] I had first befriended. He was a man who cared for the poor and the underprivileged — so much so, he would stop key conversations with colleagues if a beleaguered auto-rickshaw driver happened to approach him. He was a man who quit a reasonably well-paying job to work in the Sundar Nagari slums. He was a man committed to changing the nation, without any desire for power or any inclination to engage with messy politicking.

Yet, by 2014, the same man had surrounded himself with unsavoury people, built a coterie, and abandoned all that we had stood for.

What just happened?

Having closely observed Arvind, I think that some of his biggest failings have been his insecurity, impatience, anger, lack of faith in others and most importantly the arrogant belief that he knows best, and worse, that no one else does.

Since Arvind believed he had the answers, he came to view most people as expendable. In the first NC meeting after AAP’s creation, Arvind had said: “This party is not the property of 300 founding members but of the lakhs and crores of people in this country.” This refreshing stance shifted over time, got corrupted by power… till, one day, the party became the domain of a small clique. Unilateral decisions soon became AAP’s hallmark. And gullible volunteers and the media were manipulated to show Arvind in the light that he wanted to project.

The first turning point, that changed Arvind’s approach entirely, was AAP’s 28-seat conquest in the 2013 elections; it was an episode that made him confident of his ability to win elections. The second turning point was when he listened to Shanti Bhushan and others and tried to campaign across 400 Lok Sabha seats; he may have fared miserably, but now, his ambitions had been stoked. The final turning point was 2015, when he won big after sidelining all senior leaders and taking almost all decisions with is coterie. Now, he was convinced that he did not need anyone and he alone knew what was best.

Arvind told me, “I do not want intellectuals in the party, just people who say ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’.” Much like Anna who used to assume that the IAC movement circled around him — that he was IAC — Arvind started believing he was AAP, and everyone else was merely an extension of his image. If party members protested, they were to be removed — which is what happened to both Yogendra Yadav and Prashant Bhushan. If volunteers left, it was absolutely okay — “Ek jayega to dus ayenge,” Arvind used to tell me — “If one goes, ten will come forward as replacements.” From the outset, he was clear that people and principles served a purpose — and they could be discarded once the purpose was served. This stance only grew more ruthless with time. What emerged, consequently, was a coterie of yes men. Instead of debate, there was constant assent. Instead of a discussion of ideas, there was talk of the doings and misdoings of others.

The megalomaniac in Arvind gained ascendance. “Modi and the Congress are evil,” he seemed to say, “and unless they are removed or replaced by me, the country will collapse. I am the messiah who can deliver.”

And to deliver, he believed the ends justified the means. If principles had to be compromised, so be it. The larger goal mattered. “One cannot have too much idealism, one needs to be practical,” Arvind would say.

But beyond pragmatism, what seemed to grow in Arvind was the desire for power. He had flirted with it already — and now, he couldn’t conceive of a future without it. During a meeting where we opposed AAP’s proposed dalliance with the Congress, Arvind shouted: "If we do not do something, we will become an NGO!" That is when I saw the writing on the wall: he was willing to go to any length for clout. Like a businessman counting his money, Arvind began calculating votes all the time — with people reduced to the constituencies they could bring in.

At such times, I was reminded of the IAC days. When a decision was taken to withdraw the call for donations (we had collected enough to sustain the movement), and a few workers protested, Arvind said, “We are not shopkeepers or businesses to collect money for the future. If our movement is good, people will give money whenever we ask. And if it isn’t, what reason do we have to exist?”

As I saw Arvind surrounding himself with a clique, using the resolve I had once admired to capture power within the party, and moving away from a vision of alternative politics, I was left distraught. Someone had to speak up.

For me, personally, the “up” in AAP does not signify electoral victories. Rather, it connotes a battle for the nation, for integrity. Lalu Prasad Yadav wins elections; so does Mayawati; the Congress ruled for over six decades. For me, electoral victories have never been the parameter for being “up” or “down”. A party that fights for the truth, no matter the cost, is “up”.

The “down” points to the loss of a moral compass.

The way I see it, a downward slide is in progress within AAP.

This is not an epitaph of this young fledgling party, which has shown a beacon of light to the nation. It is a transitory state of affairs, which can still be corrected. The future will determine whether the party will continue to slide as it tries to expand its footprint beyond Delhi and Punjab. It could either get into a “mahagathbandhan” with tainted parties, and become one of them; or it could do a course correction, return to its core concepts of nation-building, and tread alone on its path to redemption. Whether “AAP and Down” becomes “AAP and Down and Still Further Down” or “AAP and Down and AAP” remains to be seen.

What also remains to be seen is whether Arvind learns to function as a leader should. Like Anna and Kiran Bedi, Arvind has been functioning at the gut level. Anger, jealousy and impatience have been a part of his operating style. However, for any major transformation to take place, I strongly believe that decisions should be driven by the intellect.

The nation has been looking for a statesman in Arvind. Who is a statesman? Someone who is interested, not in himself, but his constituency; who displays the qualities of balance, calm and intelligence; who cultivates a team of qualified people with independent opinions; who has the courage to cultivate and assimilate different viewpoints; and who, most significantly, stands steadfast by core values.

Instead of a statesman, the nation has got a politician in Arvind — someone who flip-flops on issues; succumbs to rage and impatience; and chases one goal alone — getting elected. Arvind’s motives are not evil. But desperation for power has made him and his coterie adopt morally questionable modes and stances.

I’m often asked, “What do you think will happen to AAP in the future?”

In my view, AAP will remain a potent force in Delhi — after winning 67 (of 70) seats and 54 per cent of the votes, it cannot but have a firm footing in the capital. While it has lost a chunk of the electorate due to the scandals, scams and fights that have come to light, its work in the space of education and health has been noteworthy, and this might still ensure that a sizeable number of voters vote for the party in the future. What might also hold AAP in good stead is that it has addressed the needs of the poor, be it by reducing the power tariff or by lowering water bills.

Beyond the capital, AAP had an opportunity in Punjab — but this was frittered away. Now, without a strong leader in the state, and without a discredited Akali-BJP combine to secure anti-incumbency votes, AAP’s chances of becoming a potent force in Punjab seem dim. The Gurdaspur assembly bypoll of October 2017, where AAP fared miserably, is perhaps a sign of the times.

As for expanding its footprint across other states, a lot depends on whether AAP soul-searches and realigns itself with its core values. AAP’s model of controlling and running the party from Delhi has been a proven failure, and is likely to come in the way of securing any major election beyond the borders of the capital.

AAP’s task of becoming a national force is complicated by the fact that the BJP has been gaining ground rapidly after its 2014 victory. It has begun asserting itself in parts of India where it has had a marginal presence so far — be it the South, the East, or the Northeast — and is well on its way of becoming a pan-India party. Whereas, traditionally, the BJP’s appeal had been restricted to upper/middle class Hindus (and the Congress has found supporters in the SC/ST and minorities segment), the BJP has now tried winning the trust of the backward classes and the poor. Indeed, the selection of a Dalit president is proof of the party’s desire to be perceived as inclusive. That the party has a strong network, right down to the polling booth level, makes it a behemoth that will be hard to conquer.

That said, despite its obvious strengths and the rapid expansion of the party, the BJP’s failure to meet its promises of “acche din” has created a feeling of disenchantment among voters. Corruption continues unabated, and communal and caste politics rule the roost. Even as the BJP flounders, the Congress seems more and more like a party without a leader. The Left is left with a failed ideology.

There is an opportunity to fill the vacuum. Will this challenge be taken on by the Congress or AAP or someone else? That is the big question.

Right now, it seems as if AAP will remain no more than a regional power — much like Mamata Banerjee controls West Bengal, or Jayalalithaa once led Tamil Nadu, or Amarinder Singh administers Punjab. Indeed, this might be AAP’s best hope.

If AAP manages to become the ethical political party the country yearns for, the scenario might well change. In fact, after every show of the film on AAP, An Insignificant Man, the audience would break out into a spontaneous applause. Nothing could signify the underlying desire for change better.

Hypothetically, what would I do if I were Arvind Kejriwal and wanted to regain the support of the nation?

To begin with, while remaining the convenor of AAP, I’d resign as the chief minister of Delhi and hand over the reins to Manish Sisodia. I’d recognise the quantum of work that still needed to be done to consolidate the party’s position across vast swathes of the country; I’d realise that I’d be able to focus on this only if I relieved myself of the responsibilities of a top post. I’d have a one-man one-post policy in the party.

I’d call for a meeting of supporters in Delhi and apologise to them, as also to volunteers and donors, for some of the ill-thought-out decisions of the party. I’d request all IAC volunteers and old AAP members to return to the party’s fold. I’d personally meet Prashant Bhushan and Yogendra Yadav, let go of past anger, express regret, and ask them to join forces with me.

I’d appoint a team for each state. As the convenor, I’d travel to each of these states to meet volunteers and strengthen the party’s organisation; I’d also hold internal elections right down to polling booth level, and entrust key responsibilities to local leaders to empower them. I’d be firm that state elections cannot be fought without a robust organisational base. I’d start small — by fighting Zilla Parishad and Municipal elections. I’d recognise that age and time are on our side, and wisdom lay in building the party and the nation step-by-step after great deliberation, without compromising on principles.

I’d restructure the PAC. I’d remove some of those who had consistently failed the test of integrity and efficiency as well as issue a strong message against corruption by taking decisive penal action against offenders. I’d replace wrongdoers with new, capable, honest people. Merit, not loyalty, had to guarantee growth within the party.

As a corollary, I’d surround myself with those who displayed guts, courage of conviction, and the ability to put forward clear views. Those with opinions unlike my own would be treated as allies rather than adversaries.

I’d also appoint a two-tier Internal Lokpal — the first tier to examine the seriousness of the complaints against MLAs and senior members of the party, and the second tier (comprising a three-member Lokpal) to investigate and pass judgement.

I’d reinstate the donor list on the party website.

I’d work on our communication and, at all times, keep anger and impatience in check. I’d recognise that I was now a part of the system that I wished to reform from the inside — no longer could I act as the "outsider" making unsubstantiated allegations. My task, while in power, was to display maturity and strong leadership. My task, while out of power, was to act as a diligent but responsible opposition, criticising the ruling party only when the situation demanded negative feedback. Balance was key.

The aim was not to attract media attention by entering a negative news cycle; the aim was to do good work, so the press would be compelled to approach us. To this end, it was vital to regularly interact with the media, answering their queries and taking journalists with me on a journey to propel change.

Most of all, I’d create an agenda for alternative politics. I’d remind volunteers that power would come to us as long as we continued working hard and working ethically. I’d repeat JP’s slogan: "The solution to bad democracy is more democracy."

I’d remind myself: there are no shortcuts to nation-building.

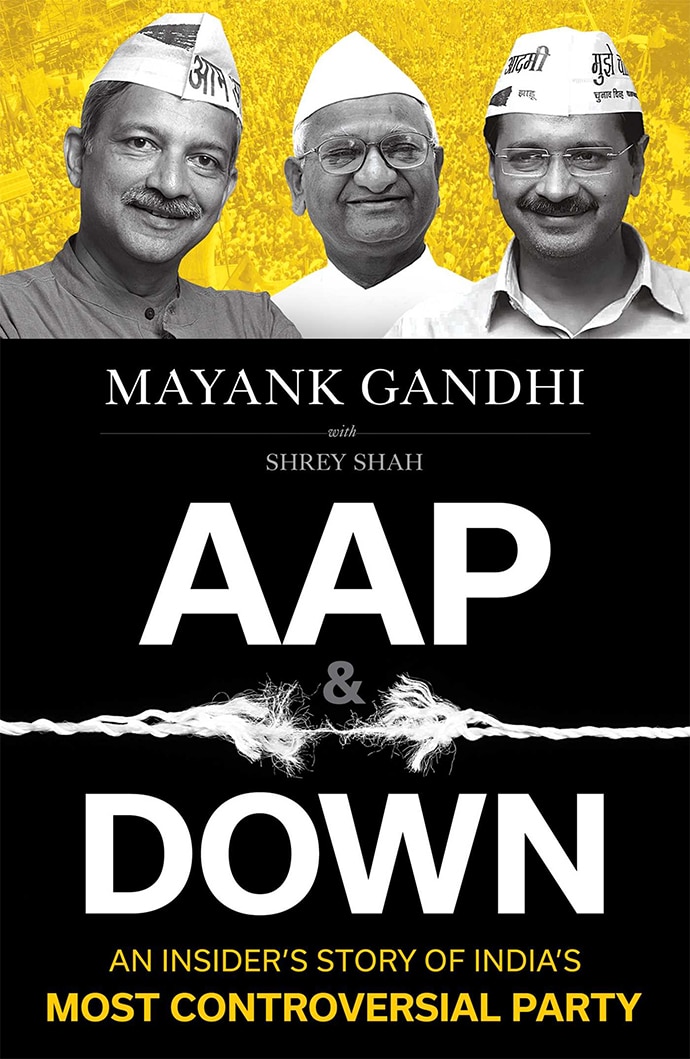

(Excerpted with permissions of Simon & Schuster from AAP & Down: An Insider’s Story of India’s Most Controversial Party by Mayank Gandhi and Shrey Shah.)