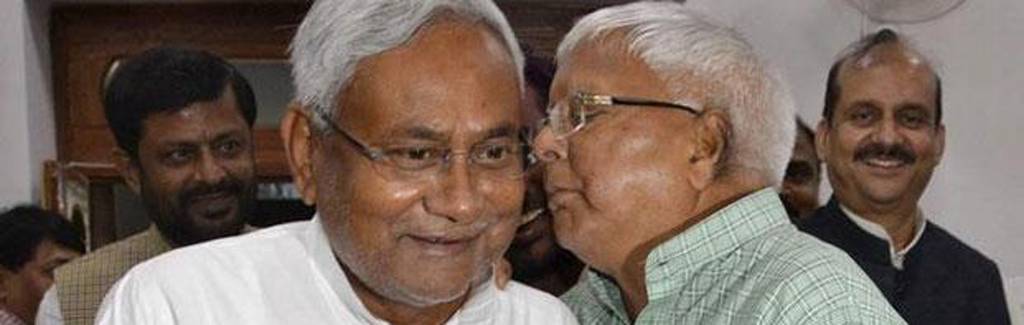

How Lalu-Nitish's doomed alliance has cut the Bihar story short

When Nitish Kumar stitched together a mahagathbandhan for the 2015 Bihar Assembly election, he had one overriding goal: to defeat his former alliance partner, the BJP.

Two tertiary ambitions drove Nitish into the arms of his decades-old rival Lalu Prasad Yadav. First, an obsessive desire to cut Narendra Modi down to size. Second, leading a national mahagathbandhan to victory in the May 2019 Lok Sabha election and dethroning Modi as prime minister.

|

| Nitish's two tertiary ambitions that led him to forge an alliance with Lalu in Bihar lie in tatters. |

Nitish achieved his primary goal last year by leading the JD(U)-RJD alliance to a landslide win and retaining the chief ministership.

Lalu, out on bail following his conviction in the 1996 fodder case, was disqualified from contesting the Bihar election but promptly installed one of his sons (26-year-old Tejashwi) as deputy chief minister and another son (28-year-old Tej) as health minister.

A visibly uncomfortable Nitish could only offer a weak smile during the swearing-in ceremony at this naked display of nepotism. The Bihar mahagathbandhan government was doomed from that moment onwards.

To recover a semblance of authority, Nitish moved quickly to fulfil his election manifesto promise by introducing prohibition.

Banning alcohol has failed in every state it has been imposed. Gujarat is a prime example. Liquor has gone underground; bootleggers are profiteering; excise revenue has fallen; funding for social welfare schemes has become scarce.

The same scenario is unfolding in Bihar. Annual revenue is estimated to fall this year by over Rs 4,500 crore. For an impoverished state like Bihar where barely 20 per cent of households have indoor toilets, that spells bad news.

Gujarat has over the decades managed to make up for lost excise revenue from prohibition with rapid industrialisation. It has high GDP growth on a large economic base and is relatively urbanised. For Bihar, though, prohibition could be fiscal suicide.

Meanwhile, Nitish's two tertiary ambitions that led him to forge an alliance with Lalu in Bihar lie in tatters. He has neither been able to cut Modi down to size nor is his dream of leading a national mahagathbandhan in 2019 likely to be realised.

The Don cometh

The release of underworld don Mohammad Shahabuddin on September 10, 2016 all but put paid to Nitish's prime ministerial ambitions. As he swaggered out of jail after 11 years of incarceration, Shahabuddin mocked Nitish as a "CM of circumstances".

RJD leaders were equally dismissive of Nitish. Raghuvansh Yadav said: "Lalu Prasad is our leader and there cannot be a debate on this. The leaders of the alliance partners decided on making Nitish Kumar the chief minister (even before the election). I didn't favour it."

Mortified in private, but putting up a brave face in public, Nitish said: "I don't care what people think - let then say what they want. Everyone knows whom people have given the mandate. I have never reacted to such things." To reassert himself, Nitish has pledged to oppose Shahabuddin's bail order.

The future of Bihar though is grim. Lalu's court conviction rules him out as chief minister if Nitish decides to lead a national mahagathbandhan against Modi in the 2019 Lok Sabha poll. If he wins, the electorate knows he will have to hand Bihar over to Lalu's sons, assorted uncles - and Shahabuddin.

Jungle Raj will then acquire an even more sinister meaning. With lawlessness and fiscal crisis overwhelming Bihar, Nitish's credentials as a national leader will suffer in the run-up to 2019.

To make matters worse, intra-mahagathbandhan competition lurks. Rahul Gandhi and Arvind Kejriwal fancy themselves as future prime ministers. Both will be nearly 50 years old in 2019. Neither has a chance of getting the top job.

Kejriwal has character flaws. According to AAP's former Maharashtra leader Mayank Gandhi, Kejriwal surrounds himself with mediocre people because he is insecure. Several AAP leaders face criminal charges. In Punjab, AAP is a divided house. It is diluting its already weak Delhi governance by spreading its limited talent pool to Goa and Gujarat.

Meanwhile, Rahul Gandhi's Uttar Pradesh kisan yatra may deliver little by way of electoral returns. The Congress's singleminded aim is to ensure the BJP does not come to power in UP in 2017. If the BJP wins in UP, it would smoothen the path to Modi's re-election bid in 2019.

That, in turn, would dismantle the Nehruvian ecosystem carefully constructed over half-a-century of "grace and favour" blandishments given to loyalists in the media, bureaucracy, and elsewhere. Another five years in the wilderness through to 2024 would damage the Congress, and the mini-dynasties that feed off it, beyond repair.

Battle for survival

Rahul and Sonia Gandhi, therefore, regard the 2019 Lok Sabha election as an existential battle. They would support any version of a mahagathbandhan as long as it keeps the BJP (and specifically Modi) out of power for another five years.

With Nitish unravelling and Kejriwal imploding, Rahul is looking at Akhilesh Yadav and Mayawati afresh. An SP-Congress pre-poll alliance in UP is unlikely given the bitter feud in Mulayam Singh Yadav's family. Post-poll though, all bets are off. In order to keep the BJP out of power in what may be a hung UP Assembly, the Congress is willing to offer support from outside.

An ageing, visibly tired but steadfastly loyal, Sheila Dikshit is being ferried around UP to slice the BJP's Brahmin votes. Even if the BJP emerges as the single largest party, the aim is to keep it to below 150 seats in the 404-seat UP Assembly. A Bihar-style mahagathbandan (though post-poll) would then allow, for example, Mayawati to take charge as chief minister with outside Congress support.

While these machinations may or may not come unstuck, Rahul's chances of replicating them in the 2019 Lok Sabha poll are remote.

That leaves Modi in pole position for 2019. But he will have to do better in the second half of his tenure than he has in his first half. As he told a television channel in a recent interview, he was shocked (but had so far remained silent) on the broken state of the economy he inherited from the Congress-led UPA in 2014.

Modi hinted at fudged figures in past UPA Union Budgets. It has taken over two years to set things right.

The prime minister has another two years to turn the economy around before campaigning for the May 2019 general election against a determined Opposition overtakes him.