Understanding the paradox of art

If you must look for the meaning of the word 'paradox', you will find a phrase that defines it as “we must sometimes be cruel in order to be kind”.

In a garden from where you could view the expensive and abstract artworks of famous artists, including a golden bust of an Indian woman installed in a little fountain inside the house, collected and owned by Shalini Passi, artists and curators gathered together on an October evening in an antinomic setting to listen to the vision of the fourth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale to be presented by Anita Dube.

In this sprawling plot at Delhi’s Golf Links, the curatorial note called the 'Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life' was read out to select the list of the invitees, but not before Passi’s new venture, an art foundation, was announced.

“At the heart of my curatorial adventure lies a desire for liberation and comradeship (away from the master and slave model) where the possibilities for a non-alienated life could spill into a 'politics of friendship’ ...In this dream, those pushed to the margins of dominant narratives will speak: not as victims, but as futurisms’ cunning and sentient sentinels,” Dube, who once was a member of the Indian Radical Painters and Sculptors Association in the late 1980s, read out.

The select audience raised a toast to her words.

In December, at the 'Guerrilla Girls' talk at Cabral Yard, a man raised the question whether using language in such complex ways is an art world thing.

Over the months, I have tried to understand such concept notes sent by agencies describing an artist’s work. The decorative text has mostly eluded me.

But more on that later.

The torches had been lit. The artworks acquired from those who graced the evening were on display in the house. Art needs patronage – that’s where the paradox lies. In the alienation of this garden with the artworks that marked the patron’s position of power, the class makeup of the art world, the elephant in the room was only too visible.

“I remember Guy Debord’s warnings of a world mediated primarily through images – a society of the spectacle – as I write this note. That such a society is fascism’s main ally, we are all discovering in different parts of the world today,” she read out.

As she invoked the 1967 book of Guy Debord, who was the de facto leader of Situationist International, which combined an understanding of alienation and hyperreality that was not much liked by the left, the venue itself mirrored the “society of spectacle” that Debord warned against.

American philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto once said the art world stands to the real world in something like the relationship in which the City of God stands to the Earthly City.

While the pitches for the art festivals and exhibitions are going for the deeply ethical appeal that lies in the “inclusive representational landscape”, we have to venture out and listen to the stories of oppression.

And then, offer the space to those who have such stories rather than telling them from our vantage points. The point of intellectualism is not arrogance but an urgency to understand rather than impose.

As the Kochi-Muziris Biennale entered its fourth edition on December 12 in the small seaside town of Kerala, there was an expectation that this edition would be more political than ever with Dube, whose own work explores the resistance of individuals and women against the idea of power, at the helm.

She had already said she would be concerned with the voices from the margins before the 108-day event began in Kochi, with its old industrial warehouses witnessing the interpretation of this grand claim.

The biennial form is now the most popular showcase of visual arts with more than 250 biennials operating globally as per the Biennial Foundation’s Directory of Biennials. There has been a five-fold increase over the last ten years – and at the core of this ‘biennialisation’ lies the experience economy, which is thriving across the world.

The 58th edition of the Venice Biennale, which will open in May 2019 and is the oldest biennale that started in 1895, is titled “May You Live in Interesting Times,”, which alludes to uncertainty, crisis and turmoil. Ralph Rugoff, the curator, said in his statement that “at a moment when the digital dissemination of fake news and ‘alternative facts’ is corroding political discourse and the trust on which it depends, it is worth pausing whenever possible to reassess our terms of reference.”

Dube made a similar pitch.

She spoke about connectivity and critical thinking, and in interviews about her nostalgia of her own engagement with Marxist thought and how it must be brought back because alienation is a big problem.

Of how the need for community must be recognised, especially when the MeToo movement has empowered women to speak out and her list, which included more than 50 percent women, supported her vision of inclusivity along with a few names like Kolkata-based Bapi Das, an auto-rickshaw driver who embroiders tapestries exploring his city, or Sweet Maria, a project which is an ongoing monument for a transgender woman killed in Kochi in 2012.

But there could have been more voices, more perspectives and bolder strokes on canvas.

Dube, of course, was operating under a lot of pressure because the production had been pushed back to a month because of the devastating floods.

But all that can be overlooked because the vision by a feminist woman curator was something that has been long overdue. In the last two years, the political discourse has been more about the rise of the oppressed, the fight for equality coming full circle with the Supreme Court decriminalising homosexuality in a landmark judgment and allowing entry of women to the Sabarimala temple in Kerala among other progressive decisions.

But then, art is also entwined with capitalism and whether the biennale format can contest existing power relations is a question that remains to be answered in the Indian context.

In a utopian sense, the biennales offer counterpoints to the regular programming of the “white cube” practice of the museums – and with Dube’s promise, identity politics seems to have entered the biennale at a time when KMB co-founder Riyas Komu stepped down in the wake of allegations of sexual harassment and on December 13, allegations of sexual misconduct surfaced against Subodh Gupta.

Dube has said previously she wouldn’t call the fourth edition of KMB “political” but why there are such denials in the art world is difficult to understand – especially at a time when polarisation appears to be the biggest threat facing the world.

Her note talks about “politics of friendships” and in the brief note, she strikes a lyrical note, which is decorative, yet abstract. To the uninitiated like me and thousands of others, it was a little jarring to read through the vision that was full of allusions but lacking in clarity.

In the 2016 edition of the KMB, in simple installation, the audience was invited to walk in seawater in a hall at Aspinwall House. On the walls, the 68-year-old Chilean poet Raul Zurita challenged you: “Don’t you listen? Don’t you look? Don’t you hear me? Don’t you see me? Don’t you feel me?”

Galip Kurdi, the elder brother of the drowned Syrian refugee child, is the one who was invisible to us, who wasn't present in pictures is the muse for Zurita because absence is more powerful than presence, the poet said.

To have Zurita, a communist poet imprisoned for his political leanings and works, as the opening artist for the third edition of the KMB was nothing short of a political statement. In the same space, Dube has South African artist Sue Williamson’s “Messages from the Atlantic Passage”, a large-scale installation based on accumulated records from Cape Town and Kochi on 300 years of slavery from the 16th century.

Not that identity politics was missing in the third edition curated by Sudarshan Shetty but the philosophical underpinnings made it more of an internalised attitude to “otherness” and also marked the importance of text in the visual arts scene – which can be looked at as a radical stand, too.

“Forming in the Pupil of an Eye” was my first time at any such art event – and to listen to the voices of exiled poets in a claustrophobic pyramid or to walk in the make-believe sea made me wonder about displacement and war and existentialism.

For instance, there was this young Lavni dancer, Anil Kasbe. Lavni is a theatrical genre combining song and recited poetry, dance and drama and fusing social, political and personal commentary, At the age of two, Kasbe left Manpur village in Maharashtra, learning the movements of dancers by watching them on TV.

It is a personal struggle against “boys don’t dance” and the ultimate aim is to chronicle his own story, he said. To make artworks and performances interact with each other, we put Kasbe in Zurita’s Sea of Pain. The sea is symbolic of Kasbe’s own journey, a story of migration and even of sexuality where he felt isolated and only now, he is understanding that there is more beyond gender binaries.

From where I come from, and from a reporter’s perspective – where we are looking for narratives rather than rhetoric – Dube’s curation was along similar lines, but I would have liked to see more South Asian context in the ambit of what she calls “voices from the margins”.

There are of course spectacular works like Nilima Sheikh’s "Salam Chechi", a collage of feminine bonding told through the stories of Malayali nurses. Then, there is BV Suresh’s "Canes of Wrath" where his albino peacock is a bold and striking take on the nationalist identity.

In journalism, we believe in a simple truth – show, don’t tell. And we are asked to stay away as much as we can from the use of adjectives. After all, it is visual art. Perhaps the art world could use that simple truth, too.

Across the world, many biennial curators and art festival directors take to grand political claims as they draw a list of artists and yet, they haven’t been able to move beyond the entreaties that are composed of catchwords like multiplicity, marginalised, etc.

In fact, for all its intent, the vision statement itself was marked by that characteristic obscureness of the so-called artistic practice.

As with the rest of the world, identity politics has become an important part of the visual arts world. But what remains to be seen is if we can go beyond the rhetoric and the catchwords and become the platform for dissent and critical exploration of the artist's social responsibility – as against the fascination for famous artists.

In our own exploration of voices from the marginalised sections, we came across artists with powerful narratives that seek to disrupt the status quo.

Like Birender Yadav, who grew up in the coal mines of Jharia in Dhanbad, whose work is a comment on Bhramanical fascist propaganda, which continues unchecked.

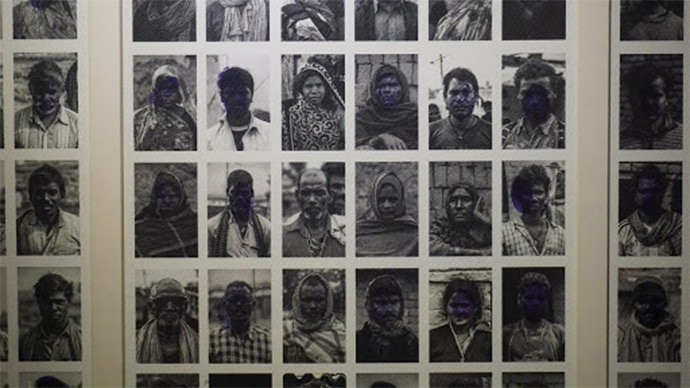

In his work, which is a documentation of the lives and practices of the workers of the brick kilns in Mirzapur in UP, he is questioning access to welfare schemes with his investigation into the lives of people in the brick kilns.

Yadav is the son of a blacksmith and graduated in 2015 from Delhi Art College. Or, the Pune-based Rajyashri Goody who says the act of eating is political and as a person belonging to the Dalit community, she feels discrimination lies in little things. Goody’s art occupies the space between personal and political.

“Unfortunately, my optimism in life is fading and I'm realising that perhaps that's just how the art world functions. The good thing is that there are more and more artists speaking about the Dalit experience with strength and pride and resilience, and as much as art institutions and galleries would like to turn a blind eye to this (because this would mean reckoning with their own caste privilege), it's getting harder and harder for them to do so ," she says.

And for a long time afterwards, I remembered stories that made me restless and question things. They were stories that were deeply personal like the one written by my former editor Rajkamal Jha of The Indian Express. It is called John Brown and a dog called Chum. In May 2002 Jha was in Ahmedabad and went to Gulbarga where a mob had burnt 38 residents alive in February that year.

“I have this terrible disease of getting distracted – looking at what’s in the margins instead of in the centre of the frame – and there was a child’s partly burnt workbook that reminded me of my childhood, when one would freeze in panic if a textbook went missing..,” he said in an interview.

Maybe you can read the story to know why I remember it years after I first read it and why it continues to make me sad. That’s how we look at the margins.